Introduction

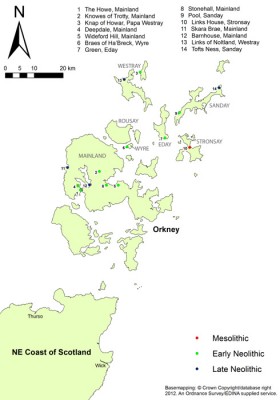

The Orkney Isles, located off the north coast of Scotland (Figure 1), form one of the most intensely studied archaeological areas in north-west Europe. Key to their continuing attraction, as a “core area” for research (Barclay 2004, 34-37), is the “almost perfect survival” of “exceptional Neolithic remains” of stone-built houses, tombs and ceremonial monuments (Parker Pearson and Richards 1994, 41; Cummings and Pannett 2005, 14). The cluster of Late Neolithic monuments - Maeshowe, the Stones of Stenness, Ring of Brodgar and Skara Brae - inscribed in 1999 as the Heart of the Neolithic Orkney World Heritage Site (Downes 2005, 2), have long dominated our understanding of domestic and ritual life.

This focus has emphasised both the chronological separateness of 3rd millennium BC Orkney, and an implied hierarchy of significance, especially with regard to these monuments and those of earlier periods (McClannahan 2006, 102). The perceived “striking and extraordinary” nature of stone-built houses and tombs has provided a powerful legacy for interpretation of the whole of the Orcadian Neolithic (Barclay 2000, 275).

However, the evidence now emerging from the 4th millennium BC – the Early Neolithic – is a picture of considerable variance in domestic architecture; importantly with the use of both wood and stone attested to in the excavated evidence. The purpose of this article is to briefly review the nature of this evidence, and to highlight the implications for locating and understanding the full variability inherent within occupation practice in this period.

An assessment of the current evidence

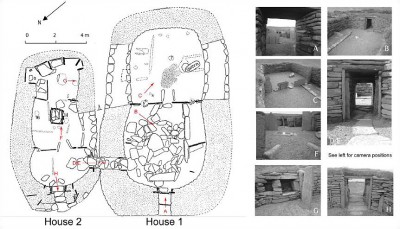

For nearly 70 years, the site of Knap of Howar, on Papa Westray, stood as the only example of Early Neolithic buildings in Orkney (Figure 2). After the area was exposed from an erosion event in the 1930s, local landowner William Traill and the antiquarian William Kirkness cleared and carried out initial excavations on these two conjoined stone buildings (Traill and Kirkness 1937, 309). Subsequently, Dr. Anna Ritchie’s excavations, between 1973 and 1975, revealed more details of the site, which she then interpreted as the farmstead of an extended family engaged in mixed agriculture (Ritchie 1983, 56-58).

Both stone-built houses are formed of double-skinned walling, cored with midden material. They are rectangular in form, with rounded corners, and sub-divided by orthostats set into the ‘pinched’ wall form. This architectural repertoire has been taken as typical, providing a blueprint for what an Orcadian Early Neolithic house “should be like” (Downes and Richards 2000, 167).

The radiocarbon assays for Knap of Howar have confirmed occupation during c.3360-3030 BC, and now a number of sites have produced very similar dates, suggesting contemporaneous occupation across both Mainland and outlying islands of the Orkney archipelago (Figure 3).

In the 1980s, Colin Richards started to re-examine the evidence for other Early Neolithic houses in Orkney, such as the structure underlying the complex Iron Age site at Howe, near Stromness (Ballin Smith 1994). This was initially interpreted as a mortuary structure, but similarities in architectural form with the Knap of Howar houses might suggest an Early Neolithic date. This is a similar situation to that found more recently at Knowes of Trotty, where a small rectangular structure underlies one of the barrows in this cemetery, constructed nearly a millennium later (Card 2005, 177; Card and Downes 2006, 27; Sheridan and Schulting 2006, 205).

Subsequent excavations on a number of sites have begun to further demonstrate the variability of occupation practice in the 4th millennium BC. The site at Stonehall, on the slopes of Cuween Hill, for instance, rather than being an ‘isolated’ farmstead appears to represent a much more clustered settlement arrangement, usually associated with the Late Neolithic, as at Skara Brae. The remains of up to seven possible houses were recorded there (Carruthers and Richards 2000, 64), within an area of 150m by 150m and with a rapid sequence of rebuilding and several shifts in settlement focus.

Perhaps the most important findings of Richards’ excavation programme, however, were the discovery of a primary timber phase of construction to the Early Neolithic settlement on the slopes of Wideford Hill, below the famous tomb. For the first time, this was unequivocal evidence that timber did form part of the architectural repertoire in the 4th millennium BC, and that traces of such structures can survive (Wickham-Jones 2006, 26).

Three post-built structures were recorded at Wideford Hill, two of similar sub-circular form (Structures 1 and 2), with a third that, at least in its latter phase, resembles a rectilinear organisation of space (Structure 3). The decaying remains of Structure 2 formed a focus for the construction of a stone-built longhouse (House 1), probably constructed whilst the decaying posts of the earlier timber structure were still in situ. This all reveals a “close grained sequence of building replacement and continuity of occupation” (Richards 2003, 6), spanning 3350 – 2920 cal BC, with a complex interplay between construction materials.

The emerging picture

Recent excavations on Wyre, a small island in between Mainland and Rousay, have revealed a similar fluid, and complex relationship between timber and stone-built elements of the architecture at the settlement of Braes of Ha’Breck (Lee and Thomas 2012). In one trench, a post-built longhouse with a central fire pit was rapidly dismantled and its posts were ripped out prior to the construction of a stone-built house on almost exactly the same footprint, although a new hearth was constructed. In another trench, a short-lived timber house, consisting of 14 post-holes around a scoop hearth, seems to have been replaced by two conjoined stone houses. Whilst post-excavation analysis of these results is still ongoing, it is clear that selection of construction material is not simply a material consideration, but also relies upon a series of socially-embedded decisions. This is of particular importance in light of recent palaeo-environmental studies, which point to the fact that Orkney may not have been as treeless in the Neolithic as previously thought, with a diverse pattern of woodland survival existing, in some areas, into the Bronze Age (Farrell et al. 2012).

It is clear therefore, that the timber buildings at Wideford Hill and Braes of Ha’Breck may be “representative of a much broader distribution” (Richards 2003, 19). This has wide-ranging implications for how such sites are looked for, given their ephemerality set against the visibility of stone in the archaeological record of the Northern Isles.

Locating Early Neolithic Orkney

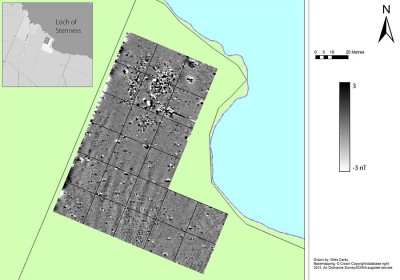

The problems in locating such ephemeral sites are demonstrated by the recent work of the author carried out at Deepdale, West Mainland. Fieldwalking had originally suggested that an Early Neolithic flint scatter here might relate to in situ structural remains, possibly of a wooden nature (Richards 2005, 16), but subsequent fieldwork has not borne this out. Through the application of high-resolution geophysical survey at this site, it was hoped that the exact nature of the settlement in this location could be clarified.

The results are consistent with midden material, a ‘signature’ also found in the geophysical survey results from Braes of Ha’Breck and Green, Eday. However, even with high resolution survey, there was no definition to these areas of magnetic enhancement, suggestive of structural remains. Therefore, debate remains over what such a lithic scatter might represent. Certainly the work has underlined the difficulty in prospection of sites of this type (Carey 2012).

Conclusions

The purpose of this brief article has been to show that the emerging picture of settlement variability in Early Neolithic Orkney needs consideration in its own right, not just as a preface to the impressive monumental Later Neolithic. The implication of the evidence requires us not only to revise the way we interpret such sites, but also the way we look for them. In particular, the unequivocal evidence for the use of timber in house construction alongside stone reminds us that material choices are not just born out of environmental necessity, but exist within a complex web of social engagements with the world in the 4th millennium BC.

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted as part of an MA dissertation at Orkney College UHI. Thanks are due to all who have allowed access to unpublished material, particularly D. Lee and A. Thomas, N. Card and J. Downes. Thanks must also be given to both Jane Downes and Martin Carruthers for all their input.

Bibliography

- Barclay, G. (2004) ‘“...Scotland cannot have been an inviting country for agricultural settlement”: a history of the Neolithic of Scotland’ in I. Shepherd and G. Barclay (eds.) Scotland in Ancient Europe: the Neolithic and Early Bronze Age of Scotland in their European Context. Edinburgh: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland

- Ballin Smith, B. (1994) Howe: Four Millennia of Orkney Prehistory Excavations 1978-1982. Edinburgh: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland

- Card, N. (2005) ‘Knowes of Trotty’ in P.J. Ashmore (ed.) Discovery and Excavation in Scotland. 177. Edinburgh: Council for Scottish Archaeology

- Card, N. and Downes, J. (2006, unpublished) Data Structure Report on Excavations at the Knowes of Trotty, Harray, Orkney. Orkney Archaeological Trust

- Carey, G. (2012) The domestic architecture of Early Neolithic Orkney in a wider interpretative context: some implications of recent discoveries. Unpublished MA Dissertation. UHI (available at http://bit.ly/NeoOrk)

- Carruthers, M. and Richards, C. (2000) ‘Stonehall (Firth parish): Neolithic settlement’ in P.J. Ashmore (ed.) Discovery and Excavation in Scotland. 64. Edinburgh: Council for Scottish Archaeology

- Cummings, V. and Pannett, A. (2005) ‘Island views: the settings of the chambered cairns of southern Orkney’ in V. Cummings and A. Pannett (eds.) Set in Stone: New Approaches to Neolithic Monuments in Scotland. 14-24. Oxford: Oxbow

- Downes, J. (2005) ‘Description and status of The Heart of Neolithic Orkney World Heritage Site’ in J. Downes, S. Foster and C. Wickham-Jones (eds.) The Heart of Neolithic Orkney World Heritage Site: Research Agenda. 20-21. Edinburgh: Historic Scotland

- Downes, J. and Richards, C. (2000) ‘Excavating the Neolithic and Bronze Age of Orkney: Recognition and Interpretation in the Field’ in A. Ritchie (ed.) Neolithic Orkney in its European Context. 159-168. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research

- Farrell, M., Bunting, M.J., Lee, D.H.J. and Thomas, A. (in press) ‘Neolithic settlement at the woodland’s edge: palynological data and timber architecture in Orkney, Scotland’. Journal of Archaeological Science

- McClannahan, A. (2006) Monuments in Practice: The Heart Of Neolithic Orkney In Its Contemporary Context. Unpublished PhD Thesis. University of Manchester

- Lee, D. and Thomas, A. (2012) ‘Orkney’s First Farmers: Early Neolithic Settlement on Wyre’. Current Archaeology. 268. 13-19

- Parker Pearson, M. and Richards, C. (1994) ‘Architecture and Order: Spatial Representation and Archaeology’ in M. Parker Pearson and C. Richards (eds.) Architecture and Order: Approaches to Social Space. 38-72. London: Routledge

- Richards, C. (2003, unpublished) Excavation of the early Neolithic settlement at Wideford Hill, Mainland, Orkney: Structures Report for Historic Scotland. University of Manchester

- Richards, C. (2005) ‘The Neolithic Settlement of Orkney’ in C. Richards (ed.) Dwelling among the monuments. 7-22. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research

- Ritchie, A. (1983) ‘Excavation of a Neolithic farmstead at the Knap of Howar, Papa Westray, Orkney’. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 113. 40-121

- Traill, W. and Kirkness, W. (1937) ‘Hower, Prehistoric Structure on Papa Westray’. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 71. 309-322

- Wickham-Jones, C. (2006) Between the Wind and the Water: World Heritage Orkney. Macclesfield: Windgather Press