Since 2011, Cambridge University has been working with the ACE (Association for Cultural Exchange) foundation in an investigation on land beside the River Granta. A fair amount is already known about the prehistoric landscape in this area, and the Bury Farm project aims to add to this an understanding of how people interacted with the river. Along the way, the partnership is developing ways of involving and teaching the local community.

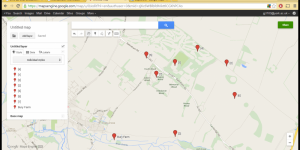

Bury Farm is located on land owned by Corpus Christi College and rented as a farm, covering the middle and lower river terraces of the Granta. It sits just outside the village of Stapleford and on the edge of the Gog Magog Downs. These low, gentle chalk hills contain a good deal of archaeological remains, particularly belonging to the Iron Age. The most significant feature is the Hill Fort on Wandlebury Hill ([1] on Map 1). This is described on the site’s English Heritage Pastscape record (2007) as a circular Iron Age fort made up of banks and ditches, which are still partly visible. Excavations in 1955 suggested that the original ditch and rampart was constructed in the 4th century BC, with refortification in the 1st century AD involving the construction of a second ditch and rampart within this.

There is evidence of intense occupation within the fortification throughout the Iron Age, including hut foundations and fragmented skeletons, as well as occupation outside the fort which predates this. There are some signs of Roman occupation on the site, and stronger evidence from across the area. A Roman road passes just to the north of Wandlebury Hill, heading east from Cambridge ([2]on Map 1), and a small distance along the river from Bury Farm a scatter of material was found which indicated a Roman building nearby ([3] on Map 1), as stated on the Pastscape record no. 371643 (2007). Extensive earlier settlement of the area is also evident. Scattered remains of Mesolithic, Neolithic and Bronze Age communities have been found, such as a Mesolithic pit ([4] on Map 1) – Monument no. 1212208 on Pastscape (2007) - and a Neolithic axe ([5] on Map 1) – Monument no. 371668 on Pastscape (2007) - both found near Wandlebury. More substantial sites are Copley Hill Farm and Little Trees Hill. Copley Hill Farm ([6] on Map 1) – Monument no. 1381680 on Pastscape (2007) - is east of Wandlebury and consists of a Neolithic long barrow and Bronze Age enclosure visible as cropmarks (Pastscape, 2007). Little Trees Hill ([7] on Map 1) is a larger hill just south west of Wandlebury. Soil marks here have been interpreted as a Neolithic Causewayed Enclosure, potentially confirmed by worked flints found nearby (Pastscape, 2007). A bowl barrow, monument no. 371693 (Pastscape 2007), sits within it.

There was clearly widespread occupation of the downs throughout most of prehistory, and the Granta will presumably have had a significant role in the landscape. Therefore, at the heart of the Bury Farm project, is an aim to understand this role – how the communities which built Little Trees and Wandlebury made use of the river and how the river effected them.

The project began in 2011 as a training exercise in test-pitting, as part of ACE’s British Archaeology Summer School. Test-pitting and augering continued into 2012 and 2013, with students from Cambridge University. Geoarchaeological surveying during this time suggested the river (which has now been channelized into a narrow stream) was once much wider and meandered across the site. Findings near the old river channel over these years consisted of some Mesolithic and Neolithic material, but hardly any belonging to the Bronze Age or later. There is some sparse evidence of Iron Age settlement and slightly more of Roman settlement, but this is far outdone by the quantity of Mesolithic and Neolithic remains. Excavations continued into 2014 in the hope of understanding why occupation seemingly declined so much, despite continuing substantially nearby.

The project was started as part of the British Archaeology Summer School, and elements of teaching have continued to be a major focus, along with efforts to involve the local community. This has evolved through the ACE foundation. The Association for Cultural Exchange is described on its website as an “educational trust” (2014) which runs and supports various teaching projects around the world. Their projects cover lots of areas, but archaeology has always been a key area for them, with one of the founding members being an archaeologist. The foundation has helped the archaeologists at Bury Farm in several ways, acting as an initial intermediary between them and the landowner and providing them with access to facilities, which make the project cheaper and more comfortable than most. Their main contribution, however, is in acting as a link with the community.

Involving the community is important for a number of reasons. There is the obvious goal of spreading knowledge and the principle that there is little point investigating something and not telling people what you have found. The community can also provide extra input, such as local knowledge and expertise from other fields. For instance, one volunteer at the site this year, a retired geography teacher, had familiarity with riverine landscapes that proved useful. Non-archaeologists can assist greatly with the project directly as well. Simply increasing the amount and diversity of people contributing to the project is always useful. Dr. Sheila Kohring, the site director, is keen to make the most of this by spending time teaching, training and building up people’s confidence.

There are three different approaches employed at Bury Farm. For the past two years, ACE have hosted an open day for locals, with an exhibition about the site and archaeology across the region, with help from the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, as well as site tours. Also, special morning sessions have been held for children between the ages of 8 and 12. The project also advertises for volunteers to work on site. The majority of these volunteers are university students, mainly from Cambridge University. They, as well as a few A level students hoping to study archaeology, appreciate the training, as do the small number of usually quite experienced local enthusiasts. Dr. Kohring says volunteering is organised differently to many other sites, as people are required to do at least a week’s work. She believes this ensures that they build up a relationship and, therefore, volunteers can contribute more.

There are, of course, problems caused by these programs. For one thing there is the problem of keeping in mind ACE’s interests. It can also be difficult, Dr. Kohring says, to manage the expectations of non-archaeologists, who sometimes imagine they will quickly uncover exciting features and date things specifically, without alienating them.

However, the community involvement is generally beneficial for everyone involved, and Dr. Kohring says they hope to continue with it (pers comm). The future of the site is still a little undecided. They intend to undertake topographic and geoarchaeological surveying for a number of years and a series of meetings are being organised with the farmer and landowner to create further plans. The community will also be involved in this decision making, through meetings to understand their views. The project needs to keep in mind the interests of many different groups, including the local community, the landowner and the Historic Environmental Record office, as well as the academic interests. Therefore, deciding its future involves much varied discussion.

Bibliography

- Ace Foundation (2014). Home Page [Online]. Available at: http://www.acefoundation.org.uk/. Accessed on: 28th August 2014.

- English Heritage (2007). Monument No. 1212208. [Online], Pastscape. Available at: http://www.pastscape.org.uk/hob.aspx?a=0&hob_id=1212208. Accessed on: 28th August 2014.

- English Heritage (2007). Monument No. 1381680. [Online], Pastscape. Available at: http://www.pastscape.org.uk/hob.aspx?a=0&hob_id=1381680. Accessed on: 28th August 2014.

- English Heritage (2007). Monument No. 371643. [Online], Pastscape. Available at: http://www.pastscape.org.uk/hob.aspx?hob_id=371643. Accessed on: 28th August 2014.

- English Heritage (2007). Monument No. 371668. [Online], Pastscape. Available at: http://www.pastscape.org.uk/hob.aspx?a=0&hob_id=371668. Accessed on: 28th August 2014.

- English Heritage (2007). Monument No. 371693. [Online], Pastscape. Available at: http://www.pastscape.org.uk/hob.aspx?hob_id=371693. Accessed on: 28th August 2014.

- English Heritage (2007). Stapleford Causewayed Enclosure. [Online], Pastscape. Available at: http://www.pastscape.org.uk/hob.aspx?a=0&hob_id=371685. Accessed on: 28th August 2014.

- English Heritage (2007). Wandlebury record. [Online], Pastscape. Available at: http://www.pastscape.org.uk/hob.aspx?hob_id=371612. Accessed on: 28th August 2014.