In recent years, there have been several discoveries in the Chalcaztingo archaeological zone which pertain to the playing of a ballgame. In one of her early forays at the site, Cook de Leonard (1967:84, Plate 8) reported upon a ballcourt marker which resembled Classic period markers from Teotihuacán. During the 1972-1980 Chalcatzingo Project, conducted under the auspices of the University of Illinois and the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, (INAH), an enclosed ballcourt at Terrace 15, Structure 2, typical of the Late Classic period (AD 600-800), was excavated on the northern side of the site’s main platform mound (Martín Arana 1987:388-389; Taladoire 2001:104-108), shown in plate 1.

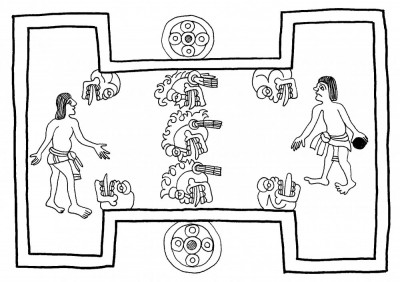

Five hand-made figurines were found under the playing alley as part of an offering, but were too idiosyncratic to associate with other figurine types present at Chalcatzingo (Martín Arana 1987:390-391). The same project also uncovered a handstone and fragments of a yugo—two stone artefacts that are closely linked with the widespread Middle Classic period (AD 300-600) ballgame cult associated with the Gulf Coast (de Borhegyi 1980:8-11; Grove 1987:336-338). Together, this archaeological data places the ballcourt at Chalcatzingo between the Middle Classic and Late Classic periods, at a time when the ballgame was reaching its apogee in Mesoamerica and new innovations were being introduced into the game such as stone rings and enclosed courts (Taladoire 2001:102, 110). Many of these changes continued to be a part of the ballgame well into the Postclassic period (AD 1200-1520), represented in plate 2.

Unfortunately, despite there being many important finds associated with the ballgame in the Chalcatzingo archaeological zone, neither of the stone rings that probably belonged to its ballcourt have yet been identified by investigators.

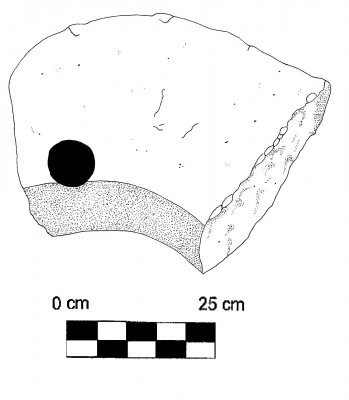

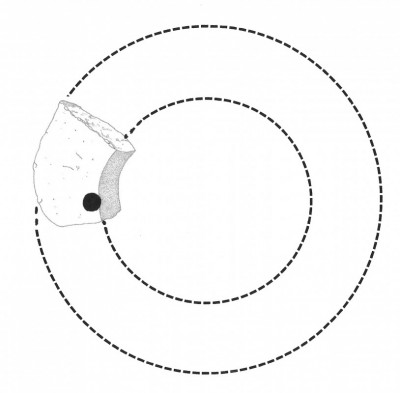

The following section explores the possibility that a sculptural fragment, currently located in the caretaker’s building near the central plaza of Chalcatzingo, is the remnant of one of these missing stone ballcourt rings (plate 3). The stone fragment in question is a ring segment made of locally available granodiorite measuring approximately 22 cm in thickness and 40 cm along the perimeter of its longest curved edge.

The fragment constitutes approximately one-seventh of a complete stone ring, assuming that it matched the form of other Late Classic and Early Postclassic period ballcourt rings in the western Valley of Morelos and the Valley of Mexico (Baquedano 1991:178; Taladoire 2001:102) (plate 4). Based on the dimensions of the segment, the exterior diameter of the complete stone ring is estimated to have been around 85-90 cm. Stone rings of a similar size are known from Xochimilco, San Francisco Asis de Xocotitlán and other locales throughout the Basin of Mexico (Baños Ramos 1990; Baquedano 1991; Nicholson 1985).

In addition to its broken state, the ring segment is characterized by a small circular cup-mark, measuring 4-5 cm in diameter. Although low-relief carvings of petaloid designs and various animal figures such as monkeys and serpents are common features in the stone ballcourt rings of Central Mexico (Whittington 2001:242-243), it is not clear whether or not the cupulate marking served a similar purpose. Rather, given that stones from the ballcourt’s balustrade were appropriated to build portions of Structure 4 on Terrace 15 (Martín Arana 1987:391), it seems likely that the stone rings, along with other elements of the ballcourt, were taken down, broken apart, and repurposed sometime towards the end of the Late Classic period. The cup-mark may be evidence of this kind of monument modification, but it is possible that the cupule was created during an iconoclastic event during the last few years of Chalcatzingo’s Classic period occupation. Regrettably, there is not enough evidence to test these different ideas. Certainly, by the end of the Late Classic period, whatever the cause, the ballcourt at Chalcatzingo ceased to be used and appears to have been replaced by a ballcourt (Structure C) at the nearby Postclassic period site of Tetla (Martín Arana 1987:396).

As ongoing research projects and excavations at the Chalcatzingo site uncover new monuments and clarify the culture history of this important ceremonial center and village, it is hoped that further evidence of the stone rings may be found. Thus far, the ballcourt at Chalcatzingo bears many of the hallmarks of cultural exchange between the societies of the Gulf Coast, Oaxaca, and Central Mexico. However, new information is needed in order to investigate whether changes in the use of the ballcourt at the end of the Classic period reflected local processes of site renewal or large-scale historical changes linked to political decentralization after the fall of Teotihuacán (Santley, Berman, and Alexander 1991:18-20).

Acknowledgments

My research in the Chalcatzingo archaeological zone was funded by a graduate student research grant from the Anthropology Department at Brandeis University. Permission to investigate the monuments and rock carvings of Chalcatzingo was kindly granted by Mario The Pre-Columbian Ballgames: A Pan-Mesoamerican Tradition Córdova Tello of the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia center in Morelos (INAH Permit No. P.A. 42/05).

Bibliography

- Baquedano, E. (1991) ‘A Stone Ring ‘Tlachtemalacatl’ from the Archaeological Museum of Xochimilco’ in van Bussel, G.W., Paul L.F. van Dongen, P.L.F., and Leyenaar, T.J.J. (eds.): The Mesoamerican Ballgame. 177-179. Leiden, Netherlands: Rijksmuseum voor Volkenkunde.

- Cook de Leonard, C. (1967) ‘Sculptures and Rock Carvings at Chalcatzingo, Morelos’ in Studies in Olmec Archaeology. 57-84. Contributions of the University of California Archaeological Research Facility, No. 3. Berkeley: University of California, Department of Anthropology.

- de Borhegyi, S.F. (1980). Contributions in Anthropology and History, No. 1. Milwaukee: Milwaukee Public Museum.

- Grove, D.C. (1987) ‘Ground Stone Artifacts’ in Grove, D.C. (ed.): Ancient Chalcatzingo. 329342. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Martín Arana, R. (1987) ‘Classic and Postclassic Chalcatzingo’ in Grove, D.C. (ed.): Ancient Chalcatzingo. 387-399. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Nicholson, H.B. (1985) A Tale of Two Ball-Courts: Laguna de Moctezuma, Sierra de Tamaulipas (TM2 304) and Ixtapaluca Viejo (Acozac), Basin of Mexico. Preliminary Paper for the International Ball Game Symposium,Tucson, Arizona.

- Nuttall, Z. (1903) The Book of the Life of the Ancient Mexicans. Part I – Introduction and Facsimile. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Santley, R.S., Berman, M.J., and Alexander, R.T. (1991) ‘The Politicization of the Mesoamerican Ballgame and Its Implications for the Interpretation of the Distribution of Ballcourts in Central Mexico’ in Scarborough, V.L., and Wilcox, D.R. (eds.): The Mesoamerican Ballgame. 3-24. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

- Taladoire, E. (2001) ‘The Architectural Background of the Pre-Hispanic Ballgame’ in Whittington, E.M. (ed.): The Sport of Life and Death: The Mesoamerican Ballgame. 97-115. New York: Thames & Hudson/Mint Museum of Art.

- Whittington, E.M. (2001) ‘Catalogue’ in Whittington, E.M. (ed.): The Sport of Life and Death: The Mesoamerican Ballgame. 137-264. New York: Thames & Hudson/Mint Museum of Art.