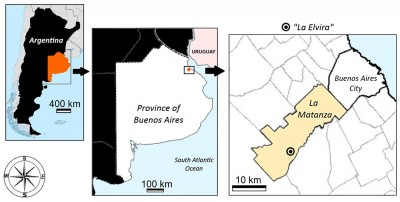

This paper describes a peculiar set of objects from the “La Elvira” site, also known as The Bicentennial House in La Matanza, the most populated county in the Province of Buenos Aires, Argentina (Figure 1). These objects were found in the last standing building from “La Elvira”, a 19th century productive ranch in the countryside near Buenos Aires City. A project was developed in order to prevent the house from being demolished, as it was considered of historical value. “The Bicentennial House” project consisted of the disassembling and transportation of all the elements of the dwelling, carried out in conjunction with an archaeological survey. During the monitoring of the former activities, the objects presented here were recovered.

The dwelling

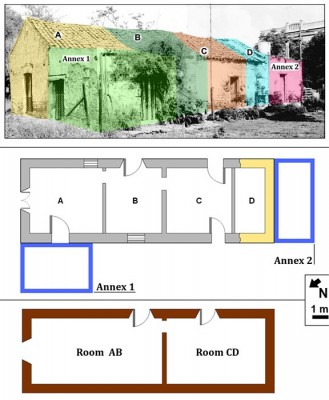

“La Elvira” site consisted of a three-room house (A, B and C in figure 2) which, according to the construction materials and techniques observed before its disassembling, was around 200 years old. A preliminary study of the changes in the structure (Ávido 2012a), the foundations and the roof, along with other features, showed that the dwelling was originally planned as a two-room house but, after the mid 19th century, it was divided into four rooms. Later, two other rooms were annexed. By 2011, when the disassembling and the archaeological survey were carried out, both annexes and room D had already been demolished.

An overview of the findings

| Collection units (C.U.) | Material Types | totals per C.U. | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vegetal | animal | ceramics | glass | metal | construction | plastic | others | ||

| Test 1 | 16 | 114 | 14 | 224 | 15 | 45 | 3 | 4 | 435 |

| Test 2 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 10 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 33 |

| Test 3 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 42 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 57 |

| Pits 1 to 6 | 4 | 17 | 2 | 30 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 66 |

| Monitoring | 2 | 23 | 42 | 309 | 21 | 4 | 3 | 10 | 414 |

| 1005 | |||||||||

| Table 1. Detail of the archeological remains from "La Elvira", per collection unit (after Ávido 2012b). | |||||||||

More than one thousand artefacts were collected during fieldwork, 61% of them glass fragments and 16% of them animal remains, while other classes were represented by less than 7% each. Table 1 shows details of the archeological remains from “La Elvira”, per collection unit. The "vegetal" category includes wood fragments, seeds and charcoal, while the "animal" category includes leather and bone fragments. Additionally, "ceramic" includes fragments of redware, stoneware, porcelain and earthenware, but excludes bricks and tiles which are counted under the "construction" category.

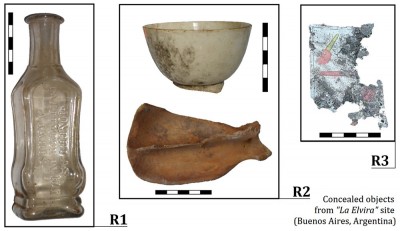

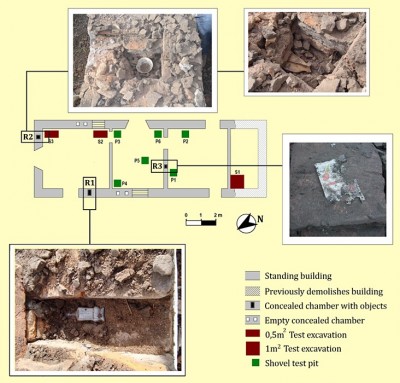

Among these findings, there were some odd ones: a glass bottle, a playing card, an animal bone and a pot (Figure 3). What was odd about them? They were found inside voids or “chambers” within the walls. These were not just voids between bricks, but structured and sealed chambers within the structure of the wall: their existence was intended. Three of these chambers, located in three different walls, contained the mentioned objects, while other chambers were empty. They could not be seen nor accessed from outside or inside the house, since the walls concealing the chambers had no marks or signals and the plastering had no cracks. Thus, we considered these objects were not accidentally there, like trapped coins between the cracks of the floorboards; the chambers and their content had more likely been deliberately concealed (Mackay 1991). Figure 4 shows the location of the chambers with concealed objects.

Deliberately concealed objects

We faced these odd findings as a novelty for South American archaeological contexts since, to our knowledge, there were no reported cases with similar attributes. Hence, in order to understand this practice, we focused our attention into previously researched cases from Europe, Oceania and North America (Ávido 2012c).

Shoes are the most commonly concealed objects, thousands of them having been recorded within the UK alone (Dixon-Smith 1990; Mackay 1991; Pitt 1998; Swann 1998; Harvey 2009). Indeed, in Northampton there is a “Concealed Shoes Index” (Mackay 1991; Pitt 1998; Riello 2009; @2) which, for decades, has been recording all the shoes reported by people who have found them at their homes or workplaces. According to this Index, there are three outstanding characteristics about the concealed shoes: a) they are in bad shape, either being well-worn before depositing or, more interestingly, having been destroyed on purpose; b) the location of the concealment is not easily reachable; and c) they are found accidentally, mostly during remodeling or other construction works (@1; @2). Similar cases were reported in Australia (Evans 2009), the United States (Manning 2011) and Switzerland (Volken 1998), though their frequency is lower than that of the UK.

In addition to the shoes, other kinds of materials were found in concealed contexts, like bottles, garments or coins, to name only a few. Witchbottles, which consist of ceramic jars or glass bottles filled with urine and nails, are considered as home-made devices for countering witchcraft (Becker 1980; Fennell 2000; @3). Some concealed contexts contained more than one item; a worth noting case is the “Bryce House” in Annapolis, Maryland (the USA), studied by Leone and Fry (1999), who found a few caches with rocks, pieces of pottery, glass, coins and animal remains (@6; @7). They suggested that, since they lacked Christian items, these caches were probably an Afro-American creation (Leone and Fry 1999; @6; @7). Dried cats have also been reported as concealed items, for they have been found hidden above ceiling boards, within walls and below floor boards (@3).

One more interesting precedent is the “Deliberately Concealed Garments” project (@1) which, as the “Concealed Shoes Index”, has developed a database for the reported findings within the UK of concealed items of clothing. Again, the outstanding characteristics of these garments are the same ones listed for the concealed shoes. They refer to this practice as folklore and superstitious tradition.

Summarizing, the preceding projects were cited in order to show the variety of reported cases of objects that have been deliberately concealed and accidentally found. Frequently, these findings are seen as ritual behavior dealing with home protection or for preventing witchcraft (Dixon-Smith 1990; Evans 2009; @3). Would this be a suitable explanation for the concealed objects from “La Elvira” site? Were they protecting the family or countering suspected witchcraft? It is certainly a tough question to be answered, since we lack documents describing the practice and its meaning. For the time being, all we can do is stress some points:

- According to the location of the caches (Figure 4), the objects were grouped in three different walls: the perfume bottle was in the NW wall, the playing card was in the SW wall, and the pot and bone were in the NE wall. All three caches enclosed the AB room (Figure 2).

- There were some empty chambers in both NW and SE walls (Figure 4). We do not know if they were meant to be empty or if it is a preservation issue.

- The perfume bottle from R1 was lying on its side, with its top NW oriented. It was filled with a sawdust-like content, which is to be analyzed.

- The pot and bone inside R2 were "mounted" one above the other: the pot was the first to be discovered and, after its collection, the bone was found (see Figure 4).

- The bone inside R2 was a canid scapula, probably from a dog. Its spine was incomplete/broken and there were several marks in the glenoid cavity. Furthermore, the pot base was broken and black stained.

- The playing card found in R3 was incomplete and lacked its backside.

- The perfume maker of the R1 bottle, a French company named Monpelas, started its business in 1830 (Rigone 2008).

The preceding list was intended to show the peculiarity of the location and content of the caches found in this site. It does not answer the problem of their function and meaning; on the contrary, it opens new questions. In-depth research will certainly show us the way to understand who did this and why. Even though all the researchers I have spoken to would ascribe this practice to African and Afro-American people, I suggest Catholic people should be considered as potential concealers as well. Regarding the symbolic component of the concealed objects, we can hardly know the meaning given in the systemic context. But we can explore existing and alternative explanations for this practice from an archaeological approach, studying the diversity of concealment items and their contexts. On the other hand, it is clear that we are bound to do what it takes to preserve these witnesses of time, for they constitute “an ‘inside out’ memory” of the building they belonged to (Eastop 2006, 251).

“When we rebuilt a 17th century Cheshire long house in 1998, the builder asked for pairs of old shoes from each member of the family. He put them up in the roof by the chimney in order to ward off evil spirits. I was more than happy to help keep alive an old tradition and gave 4 pairs of shoes to him. What will the finders say when the house is next rebuilt in about 2100?”

Comment to the note “Concealed shoes: Australian settlers and an old superstition” http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-16801512?postId=111999731

Bibliography

- Avido, D. (2012a) ‘La Casa del Bicentenario en La Matanza. Una mirada de la estructura y sus modificaciones’. Urbania, Revista Latinoamericana de Arqueología e Historia de las Ciudades. 2. 39-50

- Avido, D. (2012b) ‘Caracterización preliminar de los objetos de vidrio de la estancia “La Elvira” (Virrey del Pino, Buenos Aires)’, in A. Traba (ed.) El vidrio en Arqueología histórica. Casos de estudio en Argentina. Editorial Académica Española. 49-72

- Avido, D. (2012c) ‘Indagando una práctica escasamente documentada: los objetos ocultos en los muros de una vivienda del siglo XIX’. Actas de las Cuartas Jornadas de Historia Regional de La Matanza. UNLaM – ISFD no. 82. 587-596

- Becker, A. (1980) ‘An American witch bottle’. Archaeology. 33 (2). 18-23

- Dixon-Smith, D. (1990) ‘Concealed shoes’. Archaeological Leather Group Newsletter. 6. 2-4

- Eastop, D. (2006) ‘Outside in: making sense of the deliberate concealment of garments within buildings’. Textile. 4 (3). 238–255

- Evans, I. (2009) ‘Touching magic: a strange secret brought to light’. Trust News Australia. 1 (9). 8-9

- Fennell, C. (2000) ‘Conjuring boundaries: inferring past identities from religious artifacts’. International Journal of Historical Archaeology. 4 (4). 281-313

- Harvey, L. (2009) ‘Clogs in the wheel pit: the clogs from Woodlands Mill, Steeton’. Yorkshire Archaeological Journal. 81. 329-335

- Mackay, A. (1991) ‘Northampton Museums concealed shoe index’. Archaeological Leather Group Newsletter. 7. 3-4

- Manning, C. (2011) ‘Hidden footsteps: analysis of a folk practice’, paper presented at the Ball State University Student Research Symposium, Indiana. Available at : http://ballstate.academia.edu/ChrisManningPratt [Accessed January 2012].

- Pitt, F. (1998) ‘Builders, bakers and madhouses: some recent information from the Concealed Shoe Index’. Archaeological Leather Group Newsletter. 7. 3-6

- Riello, G. (2009) ‘Things that shape history: material culture and historical narratives’, in K. Harvey (ed.) History and Material Culture. London: Routledge. 24-47

- Rigone, R. (2008) ‘Múltiples voces en las prácticas de la toilette en el Buenos Aires del siglo XIX’. Vestigios, Revista Latino-Americana de Arqueología Histórica. 2 (2). 39:55

- Swann, J. (1998) ‘Shoes Concealed in Buildings’. Archaeological Leather Group Newsletter. 7. 2-3

- Volken, M. (1998) ‘Concealed Footwear in Switzerland’. Archaeological Leather Group Newsletter. 7. 3

Recommended websites:

- “Deliberately Concealed Garments” Project. Available at: http://www.concealedgarments.org/ [Accessed September 2011]

- Northampton Museums & Art Galleries Available at: http://northamptonmuseums.wordpress.com/2012/06/19/concealed-shoes/ [Accessed September 2012]

- “Apotropaios” Available at: http://apotropaios.co.uk/index.html [Accessed September 2011]

- “Ian Evans's World of Old Houses” Available at: http://www.oldhouses.com.au/ [Accessed December 2011]

- “Gentle Craft – Shoe Museum” Available at: http://www.shoemuseum.ch/ [Accessed February 2013]

- “Input on Tortoise Shell” Available at: http://bannekerdouglassmuseum.blogspot.com/2008/03/input-on-tortoise-she... [Accessed July 2012]

- “More on the Tortoise Shell” Available at: http://bannekerdouglassmuseum.blogspot.com/2008/03/more-on-the-tortoise-... [Accessed July 2012]